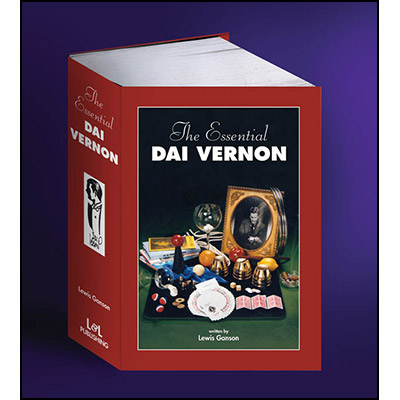

Dai Vernon Book Of Magic Pdf Free

On

Dai Vernon Book Of Magic Pdf Free 5,0/5 2871 votes

THE

DAI VERNON BOOK OF MAGIC by LEWIS GANSON Member of the Inner Magic Circle (Gold Star). Member of the International Brotherhood of Magicians (British Ring). President, Unique Magicians' Club, London

Photographs by George Bartlett

L&L Publishing thanks Excalibur Promotions Limited of Supreme House Bideford Devon EX39 3YA England for granting permission for the material in this book to- be reproduced. This material was first published by Harry Stanley's Unique Magic Studio in 1957 and later by Supreme Magic of England. The exclusive distribution rights for this title in the United Kingdom and Europe have been granted to Excalibur Promotions Limited, Supreme House, Bideford, North Devon, EX 39 3YA, England. © Copyright L&L Publishing 1994. All rights reserved. Note: The copyright of the material in this book reverts to Excalibur Promotions Limited 30.5.2014. Special thanks to Spencer Laymondfor his help and support, Anthony W. H. Brahams who was invaluable with all his help in this reprint project, also Bruce Cervon, Gary Plants, Gene Matsuura and William Bowers.

CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE.—BACKGROUND TO A LEGEND. A short biography of Dai Vernon—a magician who has become a legend in his own lifetime. CHAPTER Two.—THE VERNON TOUCH. Dai Vernon reveals the methods he employs for the evolution and performance of his magic—the magician's line of thought when studying a new trick—the approach to original presentation—advice on naturalness of action—adapting a trick to suit one's own style and personality—conditions of performance—practice—simplification of handling—lessons to be learnt from great magicians of the past and present. CHAPTER THREE.—A CHINESE CLASSIC. Dai Vernon's superb routine for ' The Coins through the Table '. Three coins pass through a solid table top—the handling is so natural and the method so subtle, that the effect appears to be real magic, especially when the magician repeats the penetration under seemingly impossible conditions. CHAPTER FOUR.—PENETRATION OF THOUGHT. A card which is merely thought of by a spectator passes from a packet of cards held by the performer to another packet held by the spectator. An intriguing feature is that the spectator does not reveal the name of the card until the last moment, when a card with a different coloured back is seen to have appeared in the packet he has been holding. When turned over, this card proves to be the one just named. An original Dai Vernon effect brought about by subtle means. CHAPTER FIVE.—THREE BALL TRANSPOSITION. Dai Vernon's famous routine in which three solid balls travel mysteriously from one hand to the other. The effect is repeated continuously with interesting variations ; even when balls are placed in the pocket, they travel back into the hands. Finally, the balls vanish completely. The moves are so cleverly conceived that, although the handling is simple, the effect is truly magical. This routine is suitable for performance as a close-up item or before quite large audiences, as two spectators hold a close-mesh net stretched between them into which the balls are allowed to fall. This enables the effect to be clearly seen and appreciated from a distance.

CHAPTER Six.—APPLICATION OF THE TENKAI PALM. The clever magician, Tenkai, has evolved a unique method for palming a card. By employing this method of palming, Dai Vernon has originated two new sleights. One is a startling colour-change which he has called ' SVENGALI ' because the card seems to change through an hypnotic gesture, and the other is a subtle method for secretly exchanging one card for another. By utilizing the latter sleight, he has built a routine, the basic effect of which is the transposition of two cards. Only two cards are seen the whole time, a Jack and an Ace—the Jack is rested against a wine-glass on the table but jumps back to the hand of the performer — hence the title 'JUMPING JACK'. This is the routine which has brought so much comment from well-informed card specialists—many contending that the effect could only be brought about by the use of a mechanical ' hold-out '. Here is the true method revealed in print for the first time. CHAPTER SEVEN.—THE LINKING RINGS. Delightful moves with the Linking Rings which will enhance any routine. These include SPINNING THE RINGS—when a single ring is linked to the key-ring, this move makes it appear that the performer spins both rings ; THE CRASH LINKING—rings are linked together through any point in their circumference ; THE PULLTHROUGH METHOD OF UNLINKING—a spectacular method of unlinking a single ring from the key-ring, the appearance being that one ring is actually pulled through the other ; THE FALLING RING— the top ring of a chain tumbles down from ring to ring until it spins from the bottom ring.

CHAPTER EIGHT.—SEVEN CARD MONTE. From a pack of cards, six black cards and a red court card are dealt in a row, face up, on the table. The red court card is in the centre of the row. Three of the black cards are turned face down ; the packet of cards is squared, then turned over. Once again the cards are placed on the table, but this time, of course, the face of the red court card will not be seen, as it is now one of the face-down cards. A spectator is asked to place one hand over the remainder of the pack of cards, then to guess which is the court card—he fails three times. Because each card has been turned face up after the spectator's choice, all cards are now face up—the court card has vanished, but when the spectator lifts his hand, that card is found on top of the pack. The effect is repeated, and, and even though the spectator tries to catch the performer by peeking at the top card of the pack, the court card vanishes once more and is found on top of the pack. It would be difficult to find a card trick which can be performed under such conditions to equal the effect of SEVEN CARD MONTE. CHAPTER NINE.—QUICK TRICKS. Often some small piece of trickery will steal the limelight from more elaborate illusions. This chapter contains several tricks which, although the performing time is short, are extremely effective. 8

LEIPZIG'S COIN ON THE KNEE. This unusual method of causing a coin to vanish is particularly effective and amusing. MARTIN GARDNER'S CIGAR VANISH. A lighted cigar vanishes from under a handkerchief by one of the ' cheekiest' moves ever conceived. DAI VERNON'S FIVE COIN STAR. Five coins appear, each one seen separately between the tips of the extended fingers and thumbs of the hands which are held together, palm to palm—the handling has been so simplified that it can be learnt quickly. DAI VERNON'S 'PICK OFF PIP'. Showing a three-spot card on the face of the pack, the performer picks off the centre spot. DAI VERNON'S ADAPTATION OF BILL BOWMAN'S ' CLIPPED '. A trick with a story in which a note secured by two paper clips and a loop of string comes free, leaving the clips and loop all linked together. CLIFF GREEN'S MULTIPLE COLOUR CHANGE. The face card of a pack changes rapidly time and time again. MALINI-VERNON 'THREE COINS FROM ONE'. A borrowed coin has two other coins '* broken ' from it—a wonderful example of maximum effect achieved by simple means. CHAPTER TEN.—EXPANSION OF TEXTURE. Dai Vernon's original routine, in which a copper and a silver coin are placed inside a handkerchief, the corners of which are held by a spectator. At the request of the spectator, either the copper or silver coin is removed magically, leaving the remaining coin to be removed by the spectator. Offering to reverse the process, the performer places the silver coin only in the handkerchief, then asks the spectator to grasp the coin through the handkerchief and hold the four corners of the handkerchief in his other hand. Taking the copper coin, the performer causes it to vanish, when it is heard to clink against the coin in the handkerchief. On opening the handkerchief, the spectator finds both coins inside. A classical effect achieved by subtle and simple moves. CHAPTER ELEVEN.—THE CHALLENGE, In this fine effect, the performer shows the faces of two cards, then places them about two feet apart, face downwards, on the table. A spectator is requested to think of one of the cards and the performer wagers that he will state which card is in the spectator's thoughts. At the outset, it appears that the performer is merely taking a two-to-one chance, but when, as the effect is repeated, he is constantly correct, the mystery deepens, especially as no questions are asked throughout the demonstration. In addition, there is a novel and amusing climax to the trick which builds it up into an exceptionally strong item. This is one of Dai Vernon's tricks which is a particular favourite with his friend Faucett Ross.

9

CHAPTER TWELVE.—DAI VERNON'S DOUBLE LIFT. The Double Lift is one of the most useful sleights in card magic. Dai Vernon reveals his own method, which allows the cards to be handled in an apparently casual and natural manner. CHAPTER THIRTEEN.—THE CUPS AND BALLS. Here is Dai Vernon's wonderful routine in which there is no over-elaboration ; it has been kept simple, both in plot and handling. The audience is in no doubt as to what has happened or is happening, although they are given no clue as to how it is accomplished. Everything appears to be free from trickery, the props are simple, the movements of the performer natural ; there is no clever hand-play which could be interpreted as sleight of hand, so that, as each phase of the plot unfolds, the audience becomes more bewildered. When finally the cups are lifted to disclose an apple, an onion and a lemon, then they are prepared to admit that they have witnessed the ultimate in magic. Surely this is the finest routine with the Cups and Balls ever evolved. CHAPTER FOURTEEN.—NATE LEIPZIG'S CARD STAB. It was Dai Vernon's particular wish that this chapter should be included in his book, as he was anxious that certain subtleties that Leipzig disclosed to him, and which had been omitted from previously published versions of the card stab, should be credited to the originator. This is the true version of the Leipzig Card Stab as taught to Dai Vernon by Leipzig himself. The originator left nothing to chance in his magic and included no difficult sleight of hand. His effects were obtained by subtle methods and naturalness of action, and this routine exemplifies Leipzig at his very best. CHAPTER FIFTEEN.—TIPS ON KNOTS. Interesting and entertaining magical effects, in which knots apparently tie and untie themselves, are popular features in many performer's acts. In this chapter Dai Vernon reveals three original knot effects. DAI VERNON'S FALSE KNOT. A knot is tied in the centre of a silk handkerchief. The performer strikes the knot with his extended forefinger, which causes the knot to vanish. DAI VERNON'S METHOD FOR UPSETTING A SQUARE KNOT. A new and natural-looking method for upsetting a knot. Ideal for such tricks as The Sympathetic Silks, Multiple Knots, etc. SPLITTING THE ATOM. Two silks are firmly tied together; a click is heard and the knot splits in two, causing the silks to fall apart. CHAPTER SIXTEEN.—SIX CARD REPEAT. Dai Vernon's entirely new and original method for performing this popular and entertaining card trick, in which apparently no matter how often the performer removes three cards from six he stiJl has six cards left. 10

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN.—FREE A N D U N L I M I T E D COINAGE OF SILVER When Dai Vernon performs this trick it causes a riot of fun. He reveals his own simplified handling of the moves by which he causes coins to appear under several articles on a table. His climax is particularly entertaining, as coins apparently appear faster than he can pick them up and stuff them into his pockets. CHAPTER EIGHTEEN.—MENTAL SPELL. After shuffling and cutting the pack, the performer removes ten cards, which he hands to a spectator with the request that any one card be thought of. Now the spectator is asked to mentally spell the name of his card. This is done without a word being spoken, the spectator removing a card from the top of the packet and placing it on the bottom for every letter in the name of his mentally selected card. At the conclusion of the mental spell, the performer reveals the spectator's card in a startling manner. CHAPTER NINETEEN.—POT POURRI. This chapter contains several items of Dai Vernon's magic which are either not complete tricks in themselves, or, if complete, are not of sufficient descriptive length to form a chapter on their own. DAI VERNON'S CLIMAX FOR A DICE ROUTINE. A beautiful series of moves which provide an excellent climax for any dice routine. DAI VERNON'S ' ONE UNDER AND ONE DOWN '. A spectator hands the performer ANY ten cards from the pack, then names any one of them. Leaving the cards in exactly the same order as they were handed to him, the performer places the top card to the bottom and the next card on the table and repeats these actions until one card remains. It is the named card. CHARLES MILLER'S CUPS AND BALLS MOVE. A beautiful move which can be incorporated into any Cups and Balls routine. Originated by this fine magician, who is a great friend of Dai Vernon. WELSH MILLER'S CARDS A N D MATCHES. A fine routine with three cards and three match-sticks. The matches vanish, appear and multiply under the cards in the same way as the balls in a Cups and Balls routine. An excellent item of impromptu magic. TIPS FOR EXPERTS. Dai Vernon reveals several all-important but little known tips for the improvement of certain sleights with cards and coins. CHAPTER TWENTY.—BALL, CONE AND HANDKERCHIEF. This is the exquisite routine which was a feature of Dai Vernon's famous Harlequin Act. The performer removes a silk handkerchief from his pocket and draws it through his otherwise empty hands—a large white ball appears from the corner of the handkerchief. After draping the handkerchief over his left hand, he places the ball on the palm and covers it with the cone. The cone and handkerchief are tossed into the air—the ball has vanished, but is found in the performer's pocket.

II

A series of vanishes and reappearances of the ball now take place and during the process it changes colour from white to red, then back again to white. Eventually the empty cone is placed on the table and the ball is wrapped in the handkerchief—but it penetrates the centre of the handkerchief. Again it is wrapped up securely, but this time it vanishes completely. However, the ball, like a homing pigeon, has returned once more to its hiding place under the cone on the table. CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE.—THE LAST TRICK OF DR. JACOB DALEY. During the last months of Dr. Daley's life he evolved another of his excellent card tricks, which he demonstrated for Dai Vernon. Dai Vernon was a very close friend of the Doctor's, and includes this trick in his book as a tribute to a great magician. This is a routine with just the four Aces—a perfect transposition of the black and red Aces. The handling is so clean and natural in appearance that there appears to be no opportunity for trickery—a fine effect by a master magician. CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO.—PAUL ROSINI'S IMPROMPTU T H I M B L E ROUTINE. This was one of the favourite impromptu effects of Paul Rosini. A thimble jumps from the forefinger of the performer's right hand on to the forefinger of his left hand—then back and forth. The performer confesses that he uses more than one thimble—and reveals five thimbles, one on each finger and one on the thumb of his right hand. He now causes them to jump singly from his right hand on to the fingers and thumb of his left hand, and finishes by dropping each thimble singly into a glass. CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE.—THE VERNON POKER DEMONSTRATION. This is a most entertaining demonstration in which the performer offers to show the methods employed by crooked gamblers when playing Poker. Although the spectators are shown that cards are stacked during a shuffle and see the performer deal himself four Aces, they still cannot understand why those cards should turn up in the dealer's hand. However, the performer repeats the effect, and eventually every hand is a good one—but the dealer has a Royal Flush. Dai Vernon employs subtle but simple methods to bring about his effect and has evolved a routine which holds the interest of the audience from start to finish. CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR.—THE THUMB TIE. Dai Vernon credits Ten Ichi and Paul Rosini with the subject matter of this chapter, but undoubtedly he has enhanced the routine with the ' Vernon Touch '! Here is the most convincing method of all for having a spectator tie the performer's thumbs together, and a really first-class routine which has been a feature of Dai Vernon's act for many years. Every detail is given, so that there will be no difficulty in understanding every move. 12

FOREWORD Times without number during the past two decades I have been asked : ' Why don't you write a book on Magic ? ' On one occasion 1 received a severe reprimand from the kindly and well-known publisher Carl Jones (who was responsible for the publication of GREATER MAGIC), who stated that I had given him fourteen negative reasons why I had not written a book but not a single positive one. My main objection was that there was so much to be said, even on the subject of playing cards alone, that I just would not know where to begin. In addition (and more to the point), I did not feel capable of doing full justice to the almost limitless ' tricks of the trade '. About eighteen months ago, while in London with my good friend Faucett Ross, I met Lt.-Col. Lewis Ganson, and we became close friends. I had read his excellent books on magic and greatly admired his clear and detailed instructions. Faucett Ross, who is a keen observer and has read almost everything written pertaining to the art, was as equally convinced as I was that here was the man to do the writing if he were willing. By a fortunate coincidence, Lewis had decided to ask me to let him write a book about my magic, so he was not only willing, but positively enthusiastic about the idea. Moreover, he resolutely refused to accept any remuneration whatsoever ; he claimed he felt honoured to do the work. I certainly consider this a wonderful compliment and I wish to thank him and let him know how fortunate I feel. We started work almost immediately, first in London, then travelled to Nottingham, the town associated with the colourful Robin Hood, where Lewis lives. There I spent over a week as his house guest, and his charming wife Jo was most tolerant of the incessant ' magic talk '. We received expert help from Ken Scholes, whilst dozens and dozens of photographs were taken by George Bartlett, who excels in showing details in pictures of hands performing intricate moves. Since 1 returned to the United States Lewis has kept up a steady stream of correspondence, and he is as meticulous as any writer could possibly be. 13

Since I was a boy of five I have been almost passionately interested in magic, particularly that branch utilizing cards and coins, so I feel qualified to give advice on the subject. I have had the good fortune of knowing nearly all the ' greats ' over a period of fifty years. I have listened and heeded the advice of those talented and gifted performers who have been so generous to me, and in this way I have accumulated what I consider to be a number of sound ideas. The contents of this book are the result of the application of these ideas. One great regret is that I never met David Devant, L'homme Masque nor Hofzinser. When I was in my teens my four idols were J. Warren Keene, Silent Mora, Nate Leipzig and Max Malini. 1 knew them all well, and my admiration for them was due to the fact that none of them used the type of apparatus that could only have been constructed for trickery. They all did 'mysterious things '—there was little, if any, display of dexterity. Although magic was their business, they treated it and displayed it as an art. These were the things which fascinated me. Before the reader turns the pages I would like to ask a question. Why does ' practice '•' frighten so many people ? Practice can and should be thoroughly enjoyable because it brings the pleasure and satisfaction of achievement. Achievement is a universally gratifying thing, and, by practising, one ends up with something of value to one's self—and others. If skill and cleverness could be acquired for the asking, there would be little to profit anyone. Will my readers conduct an experiment ? Sometime, when alone, start trying to improve some move or sleight that has already been learnt. Experiment with it, strive to improve it by incorporating your own ideas—keep trying—it is surprising how the time will fly by, but when headway has been made a most satisfactory feeling of delight will be experienced. Even a very minor achievement is most gratifying, and, as the result has been brought about by practice, it makes practice enjoyable. Jf people just cannot derive pleasure and satisfaction from practice and are not prepared to expend the time and thought and energy required because they find it irksome, then magic is not for them— they should turn to a different hobby. The contents of this book are practical effects that have been tested before audiences for many years. The results have been good and they have been well received. My original intention was to eliminate all reference to cards. However, my friend Faucett Ross persuaded me to include a few card items. When I visit England again soon I am considering having Lewis write a card book for me. That is, if I can come to terms and he will agree to share in the rewards. In the meantime, 1 trust that readers will enjoy and use this book and find it helpful in the pursuit of that fascinating and absorbing artlegerdemain. DAI VERNON. New York City. 14

INTRODUCTION When Harry Stanley informed me that he had been able to persuade the legendary Dai Vernon to visit Europe on a lecture tour, I did cherish a faint hope that the Professor might also be persuaded to release for publication a secret or two whilst he was in England. In my most optimistic moments this hope was stretched to him consenting to my writing a small booklet containing one or two of his routines. It was rumoured that, although Dai Vernon is most generous in divulging his secrets to magicians at his lectures and will explain every detail most carefully so that the members of his audience may benefit from his wonderful knowledge and experience, it is almost impossible to get him to put those secrets on paper. It was a pleasant surprise, therefore, when he readily consented to my request soon after our first meeting. Faucett Ross, who accompanied Dai Vernon on his tour, was with us when the subject was discussed, and it was he who handed me a sheet of paper next morning at breakfast—they had sat up all night deciding upon the chapter headings! Time was short ; Dai Vernon had a full engagement book, but nevertheless was prepared to devote every spare minute to the project. Faucett Ross proved to be the ideal advisor and general manager. Harry Stanley, who had made the book possible by bringing Dai to England, now gave us the run of his studio ; Bill Ellis in London and Ken Scholes inNottingham produced tape recorders. George Bartlett was telephoned and caught the first train from Nottingham to London, bringing with him his cameras and lighting equipment. From our first intention of a slim booklet, the enthusiastic suggestions of the Professor and Faucett Ross provided sufficient material for a substantial volume to be produced. My Army leave ran out, so Dai Vernon gave up a scheduled week's holiday to come to stay with my wife and me in Nottingham, where he and George Bartlett spent their days in the photographic studio, producing more photographs to illustrate the text I was to write, eventually, from the notes made in the evening and at night as Dai Vernon demonstrated and explained his magic. When Dai Vernon continued his tour, I had a pile of notes a foot thick and a stack of photographs—but it was all there. Before me was the pleasant task of setting it down in book form. Since that time, over eighteen months ago, chapter after chapter has been written, typed by my wife, and mailed across the Atlantic for Dai Vernon to correct, observe on and return. You now hold the finished product—THE DAI V E R N O N BOOK. All the fine magic it contains has been contributed by this great magician who has devoted a lifetime to his art. Every photograph in the book is of himself or of his hands performing the hundreds of moves. It has been an honour for me to have been entrusted to write this book about Dai Vernon's magic. 1 value most highly the close friendship with him which has resulted from our association. LEWIS GANSON.

CHAPTER ONE

THE BACKGROUND TO A LEGEND Page 19

17

CHAPTER

ONE

THE BACKGROUND TO A LEGEND Dai Vernon has been interested in magic for over half a century, but, although so many tricks and sleights have been credited to him, until recently the literature of magic told us surprisingly little about the man himself. It was not until Jay Marshall published a brief biography on Dai Vernon in ' THE NEW PHCEN1X ' (No. 311) and Frances Ireland Marshall wrote two articles about him for the GEN (Vol. 10, No. 9, and Vol. 11, No. 1) was it possible to piece together the story which can be regarded as the background to a legend, for it deals with the facts of a man who is a legend in his own time. The story which follows has been compiled almost entirely from the sources mentioned above, permission having been kindly granted by the authors to quote verbatim from their writings. The gold and onyx ring worn by Dai Vernon has engraved upon it a boar's head and a staff. This is the family crest of the Verner family, and is said to have originated centuries ago when the Royal Family of the United Kingdom went on a hunting trip to Northern Ireland, the country of origin of the Verners. One of the local gentry who accompanied the Royal party was an ancestor of Dai Vernon, and at an inopportune moment he strayed away from the main party to find himself confronted by a wild boar. He picked up a stout stick and battled with the boar for an hour before killing the ferocious animal. He was knighted later, as Dai puts it, 'for killing a pig'! It was in 1835 that Dai's grandfather, Arthur Cole Verner, emigrated to Canada, and ten years later, on March 14th, 1845, was born James William David Verner. He married Helen E. Spiers, and in Ottawa on June llth, 1894, their first child was born—DAVID FREDERICK WINGFIELD VERNER—DAI VERNON, affectionately known now as THE PROFESSOR. The Professor began giving magic shows while he was still at Ashbury College in Ottawa, appearing often at Government House under the auspices of Lady Maud and Rachel Cavendish. There were also command performances for the Duke of Devonshire and the Duke of Connaught when they represented the Crown. 19

One performance was in an Ottawa church hall, and young Verner was given a very demonstrative reception at the conclusion of his show, but when he returned home he found his mother weeping. He asked what was the matter, and she sobbed : ' It was that show tonight, David.' ' But,' Dai objected, ' the show went very well.' ' That's just it, David,' said his mother. ' It was too terribly professional.' In 1912 young Verner heard that in the city there was another boy, Cliff Green, who did some very good tricks. A meeting was arranged and they began to size-up each other. It was Dai who finally said : ' I'll show you the sort of stuff I do.' He borrowed Cliff's pack, shuffled them, and said : ' Name a card.' Cliff named the Three of Diamonds, and Dai said : ' Cut the pack.' Through a freak of luck Cliff cut right at the card named. Young Mr. Verner looked young Mr. Green straight in the eye and said : ' That's what I do. What do you do ? ' Over forty years later Cliff Green still recalls that the card was the Three of Diamonds. By a similar stroke of luck Nate Leipzig was victimised. Nate had just come from South America and had an unopened pack of cards in his dressing-room. Nate told Dai to open the pack—he did and saw to his amazement that it contained two Aces of Spades. To his dying day Nate never forgot the miracles performed with his own cards by a young Canadian named Verner. Dai Verner's first trip to New York was in 1913. He had learned the art of cutting silhouettes and spent the Summer at Coney Island earning his living in this way. At the end of the season he returned to Canada and entered the Royal Military College in Kingston, Ontario. During the first World War he was commissioned as a Lieutenant in the Artillery, bm later transferred to the Canadian Air Force. When the Air Force chose to assign him to the drafting depot he availed himself of the first opportunity to be demobilised, and in 1917 he went back to New York. Bond drives and bazaars occupied a good deal of his time and magicians took the remainder. In Clyde Power's 42nd Street Magic Shop he met Kellar, Han Ping Chien, Alfred Benzon, Ching Ling Foo and Dr. Elliott, as well as many others. The next phase of his life took him to Chicago and Cincinati teaching art. Always he had the black paper and his scissors for cutting silhouettes. One night Dai was cutting ' shadows ' at a bazaar in Bay Shore, Long Island, New York. Showing nearby was Horace Goldin, assisted by Sam Margules and two lovely young ladies. The feature trick was Sawing a Woman in Half. Dai noticed that one of the petite young ladies had long, long eyelashes, and he bothered to find out that her name was Jeanne. On March 5th, 1924, Mr. David Verner and Miss Jeanne Hayes were married in New York City at The Little Church around the Corner. About this time there appeared in the magic and novelty shops a book of card tricks called SECRETS—few if any knew that the man who compiled these 25 tricks was Dai Vernon. The book was a best seller and is still in print, but Dai had sold the copyright—for 20 dollars. 20

Dai Vernon had taught Larry Grey the art of cutting silhouettes ; Larry was one of the world's best card workers, and their mutual love of magic had brought them together. In 1925 they were both cutting silhouettes for a living at the Little Blue Book Shop at Broadway and 50th Street in New York. Jack Davis had a magic and joke counter there, and in walked a young magician named Cardini, newly arrived from England. He had the harrowing experience of meeting two silhouette artists who did better card fans, sleights and magic than most professional magicians. This meeting was the beginning of a life-long friendship with Cardini, who's act Dai Vernon considers to be one of the most outstanding of all times. Some twenty years ago, whilst Cardini was fulfilling a lengthy engagement at Billy Rose's famous ' Casino de Paree ', Dai Vernon was also performing at the same Night Club, but in the role of close-up magician, doing intimate magic at the tables. Dai watched his friend's act every night for an entire month and at the end of this time told him : ' Dick, I have carefully watched your act every night and have tried to detect some spot in which it might be improved, but I cannot suggest even the slightest change or improvement. For me the act is flawless.' At the end of 1925 Dai toured a professional magic act. It featured the Al Baker Cut and Restored Ribbon, Dyeing Silks through the Hand with a fake explanation. Diminishing Cards with a regular pack ; Cards up the Sleeve ; the De Kolta Card Shower ; Wine and Water using one pitcher and one glass ; and for a finish, the Clock Dial. Jeanne Vernon pulled threads off stage. On 27th May, 1926, Jeanne presented Dai with their first sonEdward Wingfield ' Teddy ' Verner. Dai had about 3 dollars at the time, so it was back to cutting profiles. So it went from 1924 until 1935 : in the summer he cut silhouettes and in the winter he did tricks. Francis Rockefeller King managed Dai Vernon during the winter months. In 1929 he added the mask and ended his act as an old Chinese magician performing the Linking Rings. Summers he cut silhouettes in Virginia, New York, Miami, Atlantic City, Chicago, Peoria, Wichita . . . any place he could earn dollars with this art. Dai was still cutting them one day in Colorado in 1932, so Paul Fox took Jeanne to the hospital. It was on 14th August, 1932, that their second son, David Derek ' Neepie ' Verner was born. It was Faucett Ross who gave ' Neepie ' his nickname, as when Dai asked him to suggest names for his son on the day of his birth Faucett said as a gag : ' Why not call him Nepomuk—the middle name of the great Viennese card expert, Hopzinser?' He later suggested that the somewhat forbidding name be changed to ' Neepie ', and, somehow, this has stuck throughout the years. The year 1933 saw the Verners at the World's Fair in Chicago and 1934 in Wichita with Faucett Ross. This association led to the publication of a manuscript describing some of Dai's secrets, which sold at 20 dollars a copy—this was followed later by another manuscript selling at 3 dollars. The management of the magic act by Miss King terminated in 1935, but in the late thirties the Professor conceived with friends the idea of his famous Harlequin Act. This idea was big and encompassed all the arts. 21

It was to be magic, but magic enhanced with dancing, musjc, colour, lights and drama. The basis of the music was a Tchaikovsky orchestration and the magic was to interpret the music, the music to beautify the magic. Dai took ballet lessons so that Harlequin could walk like a dancer, strike graceful and interpretive poses during the routines, and move like the spirit of the music that was such an integral part of the act. The artist's original sketches of the costume were most lovely and were faithfully followed when ihe clothes were made. The satin suit was a special shade—half red and half pale green, covering only the torso. The long silk-stockinged legs were one green and one red. The huge ruff of white satin and gold almost touched the big black hat that swept in medieval splendour over the Vernon brow. For an entrance a cape 14 ft. in width-—black without and red and green within—swathed the Vernon person. For a dramatic opening effect this was flung wide open to reveal the splendour inside. White gloves were removed, tossed and changed to a dove. The dove flew high and returned to Dai's shoulder. A rope trick was done with 1-inch thick white tapestry cord. At the finish his hands stroked the rope and from it seemed to pull a white billiard ball. In the same manner a leather cone was produced and a most engaging routine followed, in which the cone was put over the ball on Vernon's hand, the hand first being covered with a white silk. The ball disappeared, the silk shaken out, and from it the ball reappeared. The big hat was tossed away, to reveal a skull cap, and on the cap Vernon stood the leather cone. The ball was permitted to penetrate the silk, and then, with flourishes of the silk and the ball, the ball finally disappeared. The cone was lifted from the head and there was the ball. Again with the cone and the ball in the hand, the ball changed colour. Then the 2^ inch ball began to appear and disappear from the pocket, then changed to a black ball with stars on it (symbolic of medieval necromancy), and finally, under the cone, the ball changed to a salt shaker. The salt trick followed with a long, long pour that looked' most magical with the aid of the many special lights. Diamond dust was used instead of salt when the act played Radio City Music Hall—for greater visibility. A fine ring routine followed with 14-inch rings, half an inch in diameter, said to have the most musical ring due to their hollow steel construction. The act ended with the beautiful ' Snowstorm in China ', and at the premiere performance in the Rainbow Room at Radio City the finish was accomplished with real live moths and butterflies. Jeanne Vernon assisted in a pierrot costume. Another assistant (soon dropped because he wrecked the Vernon apartment) was a little monkey named Compeer. The original opening had Vernon walking out with a coconut, which he threw into the air. When it came down it opened and out came Compeer. At the end of the act Compeer came out in a costume duplicating Vernon's. The act was an artistic triumph, but was never permitted to be a financial one on account of the misbehaviour of Compeer. In 1941 Dai put out SELECT SECRETS and worked on a Chinese act which was booked as Dai Yen and afterwards as Dr. Chung. This 22

act opened with bare hand card productions and embodied some of the routines from the Harlequin act. Later the Dr. Chung act was presented gratis to Dai's good friend, S. Leo Horowitz, and many elements of this act have been incorporated into Horowitz's present routine. Some of Dai's tricks were published in the Sphinx and the Jinx; but Dai was making very little money from magic, so he took a job as a tool checker on the East River Drive Project. One day he was carrying a pail of mercury across some scaffolding when the whole thing collapsed. It dumped the Professor in the East River with two badly fractured arms, eight broken ribs and severe lacerations. Recovery was slow and painful— his right arm is still stiff—but the war years found him fit again and out on U.S.O. Camp Shows. In the mid-forties he released some secrets to the Stars of Magic publications, taught sleight of hand to a few selected pupils—and cut silhouettes. In the fifties the Professor starting performing on the cruise ships going to South America and lecturing on magic between cruises. In 1955 Dai Vernon, in company with Faucett Ross, travelled to Europe on a lecture tour under arrangements made by Harry Stanley, of London. On 1st May over two hundred magicians assembled at London's Victoria Hall to see and hear the Professor. He soon got into his stride, and the audience was treated to a display of magical virtuosity — sleights, tricks and words of wisdom delivered with a sincerity that shone like the sun. What an ovation he received—it was a complete triumph for Vernon. During Dai's stay in London Harry Stanley was asked to arrange a magical entertainment at the home of Lt. Commander Robert du Pass, R.N., at which Earl and Lady Mountbatten were to be present. Dai Vernon, Jay Marshall (in England at that time and appearing at the London Palladium), Faucett Ross, Cy Enfield, Robert Harbin and myself were invited to appear. The show was a great success, and a repeat performance was requested at a later date before Her Majesty, the Queen of Sweden, and Princess Andrew of Greece. Dai put on a great act and after the main show gave an additional superb solo performance of his close-up magic for Her Majesty, and at her special request. After lectures in many cities in England and Scotland, Dai journeyed to the Continent to lecture in Amsterdam, where he was equally successful. To sum up the tour, the words of Harry Stanley are quoted from the GEN : ' He is undoubtedly the most inspiring magical experience we have had in this country for many a long day . . . his ideas and sincerity will have a tremendous influence on British magic in the future.' Dai Vernon has proved' that he was correct to concentrate on his close-up magic, in which field he has no equal. On at least three occasions in his life he has trodden the boards at the insistence of well-meaning advisers, but confesses that in each case he detested it heartily. He was successful at it, as he is excellent at anything to do with magic, but it simply was not his medium. In the unerring judgment regarding himself that he has always shown, he always ended these theatrical episodes before they had had a chance to prove themselves one way or another. He felt that if a career 23

as a stage magician proved highly successful he would, as they say, be stuck with it, and he decided he would rather just not know what the ultimate result might be. He loved close-up magic, he felt very right and in his element doing that work, and here he elected to remain. To see Dai makes you think of some slightly younger Mr. Chips—a genial, kindly soul, living in a little world apart, far from the cares and problems of the workaday world. He does not venture an opinion on politics, finance, world crises, the future or any other things that keep the rest of us in a turmoil. Dai lives while others exist, because he never worries, keeps serene and happy, and thinks only the thoughts he wishes to think. That he can accomplish this in today's world makes him even a greater magician than first suspected. Magic is Dai's world, his life, his past and his future. Except for his family, it is his love and his constant inspiration. You cannot name another so dedicated. Almost 25 years ago Max Holden wrote : ' I consider Vernon the greatest man with a pack of cards of the present day.' An old brochure heralds : ' Vernon—the man who fooled Houdini.' To us he is : THE PROFESSOR.

24

CHAPTER TWO

THE VERNON TOUCH Page 27

25

CHAPTER

TWO

THE VERNON TOUCH In the magical magazine THE GEN (Vol. 10, No. 11} the clever American magician Bill Simon wrote the following about Dai Vernon :— ' How can one person among thousands actively engaged in magiccreate so many effects, develop so many principles, improve so many sleights ? . . . I remember discussing this with Dr. Daley, one of the finest gentlemen and most skilful magicians I have known. ' How does he do it, Doc ? ' . . . f remember saying to Daley one time;' How can Dai come up with such unusual approaches all the time ?' k Well? Doc slowly replied, ' Dai not only has the background and capacity for magic, but also has a great love for the subject. When you combine Dai's knowledge and experience with his great magical drive, you get that wonderful result known as THE VERNON TOUCH: ' THE VERNON TOUCH ! That's a magical recipe. I've seen Vernon take hundreds of ordinary effects and change them into clean-cut startling miracles. I've seen complicated and difficult sleights changed to exquisitely simple handling that anyone could learn. I've seen a handkerchief and a handful of coins become a symphony of production-vanishment-penetration . . . all blended into a striking routine. How? Simple—THE VERNON TOUCH.' It was my good fortune to be able to attend most of the lectures that Dai Vernon gave on his European tour. During these lectures, in addition to demonstrating and explaining his excellent tricks, he gave his audiences a great deal of practical advice, advice which he himself had always acted upon and which was the basis of the evolution and performance of his magic. His method at these lectures was first to perform a trick, then to give a detailed explanation of how the effect was accomplished. This explanation included the history of the trick ; how the first idea was born, his train of reasoning in the evolution of the method, and the analysis he had made for examining every aspect in order to simplify the handling. It was apparent that here was no magic that was performed according to a set of instructions prepared by someone else, but magic that had been painstakingly developed by Dai Vernon for Dai Vernon. He gave his audiences his formula and assured them that if they would take his tricks, >*7 2.1

but, instead of performing them exactly as he did, would tailor them to suit themselves, altering the handling to fit their own individual styles and personalities, then they would enjoy the same success with those tricks as he had. Throughout the lectures Dai Vernon used two phrases repeatedly : ' Use your head ' and ' Be natural ', and it is this advice which, when acted upon, will enable the reader to reach a high standard in the performance of his magic ; to enrich it with that magical ingredient—THE VERNON TOUCH. Let us examine each phrase and elucidate the full meaning, the meaning which Dai Vernon emphasised both by description and example. USE YOUR HEAD. His reference is to the amount, type and quality of thought that should be applied to a certain carefully selected magical effect from the time the decision has been made to work upon it until it has reached the stage of continuously successful performance. Several examples of this need for thought were given by Dai Vernon in his lectures and in our discussions. For instance, a successful businessman gives a great deal of thought and attention to detail to problems peculiar to his own business. He is successful in business because he has studied it thoroughly and is prepared to devote his thoughts, time and talents to each and every problem that arises. If this same man takes up magic as a hobby, he may fail to realise that the same amount of thought (but along different lines) is necessary before he can perform creditably. He may give an indifferent performance because he has adopted the wrong approach to his hobby, the easy approach of giving insufficient thought to the problems that beset him. When he accepts that magic imposes certain demands for the solution of its problems, similar to those of his business, and is prepared to devote the time and thought required, then his standard of performance will improve. One of Dai Vernon's pupils was the New York businessman, Jimmy Drilling. In this instance the student realised that he had to get down to work if he was to be successful. His progress was so rapid that, although he did not take up this hobby until middle life, he has become recognised as a very fine magician—one of the very best. Mr. Drilling has a business maxim which he has found to be a wonderful asset. It is : ' Tackle the difficult problems first,' and Dai Vernon was surprised and amused when, after being shown some comparatively simple card sleights, his pupil said : ' Dai, don't bother me with the easy ones yet ; give me the really difficult ones to practise. If I can master them, then I know I can deal with the others.' Somewhat reluctantly, Dai consented, but was agreeably surprised some days later when his pupil returned to demonstrate that he could make a creditable showing with one of the more difficult card sleights—a showing of which Dai says many an experienced magician would have been proud. Dai Vernon certainly does not recommend the student of magic to attempt the difficult feats first, but quotes Mr. Drilling's experience as an example of a businessman who, finding that it suited him personally to overcome his most difficult business problems first, applied the same principle to his hobby with great success. 28

To supplement the notes taken at the lectures, we arranged for the use of a tape recorder so that Dai could elaborate on his theme in discussion with Faucett Ross and myself. It is from one of these recordings that the next examples are taken. DAI VERNON :—' Faucett, 1 think we should quote another actual instance of a magician who uses his head. As you know, in America there is a very fine intimate or close-up magician by the name of McDonald. This fellow does a marvellous demonstration of magic at a table. He is greatly handicapped by the loss of his right arm, so that all his tricks have to be performed with his left hand only. Now remember that fact, because he cannot just do a trick in the same way as another magician, everything he does has to be adapted to overcome his handicap. ' Here is how Mac sets about it—someone shows him a trick, or he reads about one, or perhaps he even thinks up an effect. He gets interested in that trick and decides to add it to his repertoire. Well, instead of sitting down immediately and starting to practise, he begins in quite a different way. ' After he has learnt the basic requirements, he mulls and meditates over that trick for several days. He walks around the streets, ponders over it, thinks about it, exhausts every possibility as to presentation, handling and actual method. ' Not until he knows every aspect of the trick and has them all clearly in his mind does he sit down and take whatever props that are necessary—a coin, a deck of cards or whatnot—and goes to work. But when he picks up those props he pretty well knows what can be done with them. He has definite ideas and he arrives at these ideas because he has made a simple analysis of all the factors that constitute his problem. ' Every magician must know the old and over-used rattle bars ; for years it has been sold, and still is being sold, by every novelty shop in England and America, until at the present moment there is not much mystery left about it in the hands of the average magician. Now in the hands of McDonald this trick takes on a new significance. Why ? Because he's used his head. He has devised little dodges, little simple methods, natural methods of handling those rattle bars, which fool well-posted magicians. ' He thought out the clever idea of placing the little fake—the little tube with the rattle in it, inside a cigarette—a lighted cigarette. He picks up a bar (one that does not rattle) and rattles it, and gets the illusion that it was the bar that rattled because he holds his lighted cigarette in the same hand. That's a good example of using one's head to devise a method, but it does not stop there. Mac does not present the trick as if it was a three card monte effect—lie has evolved quite a different presentation. ' He talks about modern methods of handling goods, transporting them from one place to another, conveyor belts, production lines, etc. He says he's found a new way of sending goods, a way which he proposes to patent. '* He opens up one of his small tubes or containers and shows a piece of metal inside and says that the metal will be transported from one container to another, then goes into his routine from there.' 29

FAUCETT ROSS :—' Yes, Dai, that certainly is a good example of using one's head—he's worked out a new approach and a new handling. ' 1 recall that in Chicago some years ago, when everyone was working the vanishing cigarette in handkerchief by the thumb-tip method, one performer had everyone fooled—they were all looking for the thumb-tip ; he didn't use one—he used a finger-tip! The magicians didn't bother to look at his fingers, they were watching his thumb—and so not only did he fool the general public but the magicians as well! ' By the way, Dai, reverting back to McDonald ; how about his Egg on Fan presentation as a fine example of using one's head ? ' DAI VERNON :—' Yes, Faucett. I'll just confine that example to the presentation side, as, of course, he uses the Max Sterling method. It's the way he presents it which shows the thought he has put into it. ' He bases his presentation on the creation of life—he does not just bounce a little piece of paper on a fan until the paper assumes the shape of an egg. He tells an interesting story about eggs, about the life that comes from an egg—he does not create life, but he does create an egg which itself contains life. His story is so good and his showmanship so convincing that people are carried away into a world of fantasy and are momentarily prepared to accept that he can do anything—even create life. ' Yes, every trick that Mac does has quite a different form of presentation to that which other magicians use—that's what makes him outstanding—he uses his head.' ' Now don't get the idea that what I mean by ' using one's head ' applies to originality in method and presentation only. Of course, one should use it for all aspects of magic ; everything we do in magic should only be done after and as the result of some pretty clear thinking. There is going to be a lot of writing done before this book is completed, and although there is no doubt in my mind that Lewis will make it all easy to understand, the reader must use his head when reading how the tricks are done—or, more important, how to do them. What I think looks right to me might not look so well in a person's hands who has quite a different sort of personality. I know that, basically, the methods and the routines are right, but everyone has a different style, so what is a natural handling to me might look unnatural when performed by someone with totally different characteristics in his general make-up. The reader will have to appreciate this and use his head when adapting the tricks to suit himself. ' I'd like you to see Tony Slydini, Lewis—he's a wonderful performer who can fool even the best brains. Why ? Because he's used his head to such good purpose that he's built his magic right into and around his own personality. Tony speaks with an attractive accent, his temperament is Latin, with the hand gestures and (to us) excitable manner that goes with it—it's the most natural thing in the world for Tony to gesture with his hands—he speaks with them. What he has done is to study himself; he's analysed every gesture he makes which is NATURAL to him and NOT altered his gestures one bit, but used those gestures as the perfect cover, the perfect misdirection for his trickery. When Tony gestures with his hands to emphasise something he is saying then that's the time to watch— although you still won't see anything you shouldn't because he has practised his art so thoroughly that he has eliminated all chance. Anyhow, it's 30

only a ten-to-one chance that he has done anything on that occasion, for, you see, his actions are identical whether there is trickery involved or not— these are natural actions, natural to Tony Slydini. ' The point 1 would like to make is that if, say, an Englishman were to perform Tony's tricks exactly as Tony does them, then he would have no chance at all of fooling anyone. The gestures which help to promote the misdirection, the excitable personality of which those gestures are part, would be entirely foreign to his natural self—the whole performance would scream of trickery—unless, of course, that person was a great actor and could play the part of Tony Slydini. However, given the same tricks and using his head so that he adapted them to his own personality and style (mind you, he would have to work hard), altering a move here and a move there to fit his own natural style, then it would be possible for him to produce similar magical effects. That is what I mean by reading your instructions intelligently, Lewis. You are writing about my tricks ; if your readers interpret the instructions correctly and use their heads in adapting the moves to suit the style that is natural to them, then they will perform good magic. Perhaps in quoting Tony Slydini as an example I have given an extreme case, but, believe me, if you could see Tony perform then you would instantly appreciate my point.' Later it was my good fortune to see Tony Slydini perform, because in June 1956 1 visited America on a lecture tour and one evening was taken by Dai Vernon to Slydini's apartment in New York. Together with Ken Brooke, Dr. Stanley Jaks and Charles Riess, we sat for five hours watching Tony perform in the style that is all his own—beautiful magic performed by a master. On leaving the apartment in the early hours of the morning, we stopped for a coffee at a small cafe. Dai was delighted to have been able to let me see for myself the points he had made on the tape-recording in London. He then added the following observations :— ' Did you notice how Tony performed under his own conditions ? Quietly and naturally he arranged for everyone to be seated where he wanted them to be. Like a good General, he chose his own battleground. If you ask Tony to do a trick when the conditions are not to his own choosing, then he will not risk spoiling his effects. He'll murmur ' Later ', then, when he has found his own spot, he'll call you over and perform near miracles. That's the result of intelligent thinking—a good lesson for the magical student—be a good General ; choose your own conditions. There is no need to insist on moving people around and making it obvious what you are doing—wait, the time will come all right if you watch for it. I've seen fine performers spoil their tricks just because they have let themselves be persuaded to perform under impossible conditions. We learn by mistakes, but the really wise ones learn by the mistakes that have been made by others.' BE NATURAL. Let us switch on the tape recorder again and hear Dai Vernon discuss his advice to ' be natural '. ' What I mean by this is ' be yourself'—watch a good performer and note that he is perfectly at ease because he is doing the things that are natural to him ; he's not trying to be Cardini, Slydini or any other of 31

the ' greats' ; he may have learnt a lot from watching and reading about other performers, but he has adapted the tricks so that they fit him like a glove ; he is master of the tricks which have been tailored to suit him—he does not try to make himself fit tricks that have been evolved by someone else. Every action he makes is a natural action, natural to him ; if he picks up an object which he is going to vanish, then he does not pick it up in a way that only takes into account the position he needs to hold it to perform a sleight ; he has altered the sleight so that when he picks up the object in the way which is natural to him it is already in position to be vanished.' Let us take an example, a simple sleight which Dai Vernon uses to vanish a small object such as one of the balls in his Cups and Balls Routine. The sleight itself is The French Drop, but instead of keeping to the usually accepted method of performance, Dai Vernon has analysed all the factors that lead up to the sleight, then simplified the actual mechanics so that in effect no sleight as such is performed. His reasoning is that, if no clue is given that a sleight is about to be performed, then the audience must be off guard. Couple with this the natural handling of the object and logical reasons for everything that is done, then the whole thing is over and done with before any suspicion can be aroused—all that remains is the effect—the first thing the audience knows is that the object has vanished. So many performers make it perfectly obvious that they are going to perform a sleight ; they telegraph the fact that the trickery is about to commence ; they make a performance of the sleight itself; a display of skill which draws attention to the fact that a sleight is being performed. A sleight should be a secret thing, unheralded, unhurried and unseen. Study Fig. 1 and see how many performers begin the French Drop ; notice how the ball is held between the right thumb and second finger in quite a natural position, but they will often pick it up quite differently, then have to re-position it, after which they hold it for a moment whilst they bring over the left hand and insert the left thumb between the ball and the fork of the thumb. Notice how the left fingers are extended and open in a most unnatural manner. The whole picture telegraphs that trickery is being done—it's unnatural. Now study the Vernon way, the way where the trickery is accomplished under cover of natural, necessary movements. When picking up the ball in the first place, he takes it between his right thumb and second finger and does not have to alter the position for the performance of the sleight. If the ball is to be taken from one hand into the other, then there must be a reason why this is necessary. In Dai Vernon's routine his wand is at the right side of the table and he is going to pick it up, therefore it is natural to transfer the ball from his right to his left hand in order to pick up the wand with his right hand. Having provided a logical reason for the transference of the ball, no suspicion can be aroused by an unnecessary action. The next action appears casual and natural—he appears to forget all about the ball itself, his mind is now upon the wand which he requires 32

for the next part of his trick. His eyes turn towards the wand, his hands move together, the left hand to take the ball from the right hand. No exaggerated movements, just a natural transference from one hand to the other. Fig. 2 shows the hands coming together ; notice the relaxed position of the left thumb and ringers. The left fingers approach the ball to take it, the left thumb goes behind and to the right of the ball but not right through the arch formed by the right thumb and ringers (Fig. 3). The ball is covered for just a fraction of a second by the left finger-tips in the natural manner for taking, but during this time the ball is allowed to fall on to the right fingers so that when the left hand moves away an empty space is seen between the right thumb and fingers. Actually at this point both hands move, the right hand turning inwards just a little, then moving to the right and down on its way to pick up the wand, whilst the left hand turns over slightly, with ringers closed as if holding the ball. Fig. 4 shows the position of the hands as they move apart. Notice the gap between the right thumb and fingers—the place where the ball was seen a moment previously ; see how the fingers of the left hand are closed, but not too tightly— a ball is supposed to be in that hand and it requires space so the action of holding an object (the ball) is simulated. The points that the reader is urged to study closely are :— (a) The ball is picked up naturally in the position required. (/>) There is a logical reason for transferring it to the other hand. (<:•) Dai Vernon forgets about the ball— his thoughts have turned to the wand and he glances in its direction. (d) The hands come together naturally ; not hurriedly. (e) There is no unnatural French Drop ' get ready '—no telegraphing that a sleight is about to be performed. The thumbs and fingers are relaxed, not held stiffly. 33

(/)The ball is covered by the tips of the left fingers as the left thumb goes behind and to the right of the ball. The ball drops on to the right fingers under the cover of the left fingers. (g) A space is seen between the right thumb and finger-tips as the hands move apart—the space was occupied by the ball a second before. (h) The left fingers are closed, not tightly, but as if holding the ball. (/) The right hand picks up the wand. It also holds the ball secretly, but as it is being used to hold the visible wand everything appears perfectly natural. (j) All that remains is for the maximum effect to be obtained by causing the ball to vanish from the left hand. I have purposely gone into great detail in analysing this simple but important operation, as that is just what Dai Vernon does with every move he makes. In performance his moves appear casual and unpremeditated, but long before the public see the finished products they are thought about, pulled apart and put together in many different ways, practised time and time again, and only included in a routine when every aspect has been covered. He advises us to ' be natural '—believe me, he does not belittle the task he has set us in acting on this advice. He knows that each and every one of us has a different problem, as no two persons have quite the same natural characteristics and have to adapt sleights to suit our own style. On one occasion I asked him how long he had spent in attempting to perfect a certain sleight that he had shown me. ' Don't know, Lewis,' he said, ' but I do know that Charlie Miller will sit up twenty hours if necessary, just making a movement look natural—and that's after he has learnt how to do the actual sleight! ' In one part of the tape recording the conversation goes as follows :— DAI VERNON :—** A lot of people might have difficulty in understanding exactly what I mean by being natural. It's very important that movements made when a secret sleight is accomplished are natural movements, but being natural also means being yourself. If you work in a conversational style, you work as you feel, you do not try to ape somebody else, unless you are playing a part. This naturalness must not be used in a narrow sense, but also in a general sense ; it must be used in everything . . . not only in the sleights, but in everything you do. ' Faucett, you have known me many many years and know my style of working ; what's your interpretation of this ' being natural' ? ' FAUCETT ROSS :—' Well, Dai, you've been doing this for so many years that your approach, your speech, your movements are exactly the same when you are performing magic as when you are doing anything else in your daily life, that's why you not only fool the public, but you fool your friends who know you intimately. ' Many magicians have difficulty in fooling their wives or their friends because anyone who is constantly with them sees them as their natural selves and knows their natural movements ; they become accustomed to all personal mannerisms. When something is done that is foreign to what would be done naturally, then it registers immediately and a clue is 34

given that trickery is taking place. Even strangers to a lesser extent sense that something is happening, because a movement that is out of keeping with the general make-up sounds a discordant note . . . it breaks the natural rhythm . . . it upsets the tempo.' When Dai was staying at my house I lent him a book which contained a simple but effective card sleight that had appealed to me. I was certain that I had learnt it in about ten minutes and showed it to him—this was at breakfast and I hurried away to my work. Arriving home about six o'clock in the evening I found Dai with the book closed, but with a new piece of beautiful magic born of the idea he had heard about many hours previously. What I had thought good was now as near perfect as was possible to make it—I would say perfect, but Dai will not have that word. Dai Vernon often referred to his friend, Francis Carlyle, as a good example of one who is natural in performance. ' Francis is the epitome of naturalness in his sleights,' Dai would say. ' He has a wonderful style of his own, in which he combines his terrific sense of humour with his tricks. He works at a somewhat accelerated speed which is in keeping with the timing of his humour, but slows down at just the right moment to get his dramatic effect. He even fools magicians with their own tricks because he has altered them to suit himself, handles them so naturally and excites his audience with his presentation.' As Dai tells us, this business of ' being natural' takes practice ; practice coupled with ' using one's head ', but practice need not be the dull pastime which many of us are inclined to look upon it. There is a terrific incentive to progress once the first glimmers of achievement are apparent. Practice becomes fascinating because achievement of any kind is extremely satisfying, and the more one achieves, the greater the satisfaction that is obtained. This does not only apply to practising sleight of hand ; practice with apparatus is just as important. On many occasions we see a trick advertised ; let us assume that it is a box of some kind or another. Many magicians will buy it, some will perform it according to the instructions, whilst others will alter it around a little. Then perhaps just one person will knock the whole thing apart, re-assemble it in a different form, weave an entertaining story around a new plot and, after much practice, perform it in such an entirely different manner that even those who have purchased the original apparatus will gather round and say : ' Where did you buy it. I must get one! ' Most things in life which appear as if they might cause us some personal inconvenience make us invent excuses why we should not exert ourselves. ' My hands are not big enough (or not the right shape) to palm a card ' is something which one often hears. Well, Max Malini had a really tiny hand ; it was the same size as Mrs. Jeanne Vernon's (Dai measured them), and her hand is so small that there is not a lady's glove made that will fit her. Malini managed—so can others if they will practise— and use their heads. Another good excuse : ' I'm a busy person ; 1 don't get time to practise.' Maybe, but quite honestly this is open to doubt. There is a saying : ' If you want a job done quickly, take it to a busy person.' A 35

really busy person has time for most things because the thing that makes him busy is that he has the will to get things done. He has schooled himself to overcome the urge to invent excuses and in consequence tackles every job with determination. Perhaps you are thinking at this very moment : ' What's the use—I will never be capable of doing Dai Vernon's tricks.' Well, it is true that Dai has devoted a lifetime to magic and has become one of the most accomplished and knowledgeable magicians in the world, but he is the one that would encourage a very busy person who is determined to be a good performer. He would tell them to carefully select just one or two of his tricks that appeal to them and which are suitable to their own style. I can hear him saying : ' Practice just those few tricks, but make up your mind to use your head—be natural.' It will not be tomorrow, but in time, providing the advice has been acted upon, those same tricks can gain for the performer the reputation of being a first-class magician. Another pearl of magical wisdom that Dai Vernon repeated for the benefit of magicians was a favourite saying of the late Al Baker : ' Don't run when nobody's chasing you.' By this Al Baker meant : ' Don't try to prove something when it is not necessary to do so.' Many magicians consider that it is desirable for even the most innocent-looking piece of apparatus to be examined. They often create suspicion by the mere fact that, in having an article examined, they suggest to the audience that the article could be faked. Perhaps the best example that Dai Vernon gave was in the use of a double-faced card. Providing the two sides of the card are never seen at once, there is no reason at all why the audience should not accept it as just what it seems to be, but some magicians will place it on the face of the pack, then perform a double lift to prove that it has a back! Why ? Even if the double lift is made perfectly, the magician has instantly telegraphed to his audience that it need not have had a back—it could have had another face! By acting in this manner a magician is challenging his audience ; he is virtually asking them to try to catch him out. Instead of allaying suspicion by acting perfectly naturally and handling faked objects as if they were innocent, he is provoking his audience into watching and doubting every move he makes. Dai Vernon had a great respect for the late Al Baker, and considers that, in addition to having been a very fine magician, he ranked with the best of American humorists. ' His timing was wonderful,' Dai will say. ' A dry, kindly humour—but the timing! Jay Marshall learnt a lot from Al and was a fine pupil. Jay has got his own attractive style now, but it was Al who taught Jay that all important timing.' Watching Jay Marshall on stage at the London Palladium confirmed all that Dai had to say about timing. It takes a terrific personality to hold that London audience—alone on stage with just a glove puppet on his left hand (the lovable ' Lefty ') Jay brought the house down. Anybody could have repeated Jay's words, but it is his split-second timing and magnetic personality which makes him a star. In my note-book I see some interesting facts that Dai told his audiences about Nate Leipzig and other great magicians. 36

Leipzig used the Peek Control, but as a peek at a card was taken by a member of the audience, he would say : ' Just think of a card.' Although the pack was broken by the spectator for the peek to be taken, and in consequence Leipzig was able to gain control over that card, by saying ' Just think of a card ' the inference was that that was all the spectator had done. The fact that the pack had been touched was forgotten and the effect was that Leipzig had been able to do startling things with a card, the name of which had only been in the mind of the spectator. Leipzig was the first magician to use this method of approach to card magic. During practice Leipzig always used wide cards in preference to Bridge cards. By learning to do everything with larger cards, he had an additional advantage if he was ever handed a Bridge pack for his impromptu demonstrations. Most card specialists adopt this procedure these days. Nate Leipzig always gave magic a great dignity. He never performed his close-up tricks unless he had the undivided attention of everybody present and was sure that they were anxious to see his work. The late Paul Rosini also made his effects important, and, like Leipzig, gave his audiences the impression that they were watching great art, not just seeing someone perform tricks. Dai Vernon loves to simplify the handling of his tricks. He tells how he studied an idea of Max Malini's which concerns forcing a card. Most magicians will have the card to be forced on top of the pack, then, before they can offer the pack for a card to be selected, have to bring the card to the centre by means of the Pass or a shuffle. Malini would have his pack on the table with the force card already in the centre, but with a ' step ' above this card. The pack would be on the table for a considerable time before he used it, the tiny ' step ' remaining unnoticed. Even if a very observant spectator did glance at the pack, it merely looked as if it was not perfectly squared—a natural occurrence. All Malini had to do when the time came for his force was to pick up the pack and secure a break under the ' step '. It was now just a question of spreading the pack for the classical force, but, as the handling of the pack had been so clean, no suspicion was aroused. Sometimes Malini would have a card palmed in his hand perhaps half an hour before he needed to use it! By palming the card before there was a likelihood of anybody knowing he had done so, he was prepared for his trickery without having to handle the pack again. Many magicians are nervous about palming a card for any length of time, but Malini would rest his hand on the table, his fingers perfectly relaxed, and seemingly forget that he had a card palmed—lie did not mind how long he had to wait for the right moment to put it to use. Dai tells of a card-sharp who did much the same thing, but he used the hand in which he had the card palmed, mainly to cover his mouth as he coughed. To his associates he became known as ' The Coughing Kid '! Our own Johnny Ramsay was one of the first magicians to exploit this technique of ' preparing and waiting '. This is the answer to the 37

question asked by so many magicians after witnessing Johnny perform the Cups and Balls : ' When and from where does Johnny get the extra ball ? ' Johnny has that ball in his hand long before it is even thought that he is going to perform the trick. Johnny Ramsay attended Dai's first lecture in England at the Victoria Hall, London. It was good to see the good fellowship between the two magicians ; each had a mutual respect for the abilities of the other. When some inner subtle secret was about to be revealed by Dai, he would look down from the platform at Johnny sitting in the front row and with a twinkle in his eye say : ' Johnny knows—he's a rascal when it comes to this kind of thing.' Dai Vernon is a master of showmanship, but today it is of the quiet type ; he gets his effect by being himself, by being natural. Some say that Dai looks like a magician ; he looks like a person who can perform wonders, but, speaking personally, he does not have quite that effect upon me. Perhaps this is because I have come to know him well, but to me he is a kindly gentleman, one whom it is a real pleasure to know. When he comes into a room it is not with a fanfare of trumpets, but his presence is felt immediately ; a magnetic personality to whom one is drawn by his warmth and sincerity. He is a ' man's man ', but he has that charm of appearance and manner which also endears him to the ladies. There is no acting here— this is Dai Vernon. Here is the solution to the terrific effect he obtains when he does perform magic, as, disregarding for the moment all the thought and effort he has put into his tricks, he is still that same sincere person, still the same Dai Vernon whom you were chatting to pleasantly a moment ago. He has not altered his style or apparently raised his voice, there are no flamboyant gestures or ' gimmicks ' to focus your attention upon him. He conducts his performance in the same style as if he were still talking to you personally ; the same warmth, the same sincerity—how could such a person be resorting to trickery ? After the performance you know in your heart that there must be some natural explanation for the wonders he has performed, but, whilst it is happening, you are carried away into a strange world where all things are possible—possible for Dai Vernon. From here onwards this book contains tricks, and in the explanation of those tricks I have endeavoured to embody all the stratagems which Dai Vernon employs to gain the maximum effect. When studying the text the reader is urged to bear in mind the information, examples and advice given in this chapter. It will pay rich dividends, as the sum total adds up to—THE VERNON TOUCH.

38

CHAPTER THREE

A CHINESE CLASSIC Page 41

39

CHAPTER

THREE